Concentration camps occur when the government in power removes a minority group from the general population — and the rest of society lets it happen. Throughout US history of roughly two hundred and fifty years, there have been times when the US ruling leaders have treated minority groups unjustly and without the sense of fairness that the founding fathers had envisioned. From the beginning Native Americans were treated as outsiders, forced to live on reservations where their lives and activities could be controlled. Slavery was tolerated for many years before African Americans were granted freedom and released from the crushing burden of physical and economic hardship.

In 1942 President Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 brought imprisonment to all Japanese Americans living on the west coast of the United States—simply because of their ancestry. Indeed, as was later demonstrated, no examples of wartime treason or sabotage were ever found to involve Japanese Americans. Today many minority groups of US citizens are at risk from prejudice and discrimination for the same reason. They have a different ancestry than “mainstream” Americans. As our nation grapples with a wide range of issues related to disturbing incidents of anti-Asian violence and other forms of racism, immigration and the status of Dreamers amid the COVID-19 pandemic, the question is, what can art bring to the table?

Shadows of the Past, American Concentration Camps, answers the question by focusing on the art of a select group of Sansei artists whose work illustrates how they view their challenging cultural, historical and political place in America. Each artist contributes something vital and unique to the collective memory and struggles of Japanese Americans and the legacy of the American Concentration Camps.

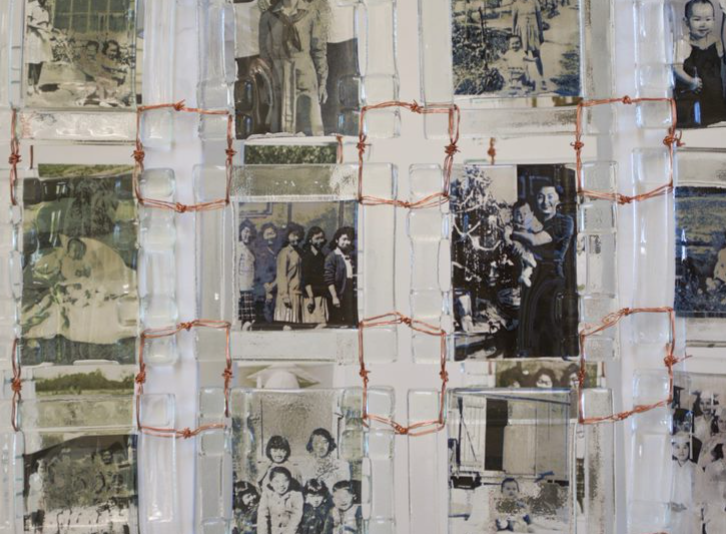

Reiko Fujii has been able to give form and definition to this difficult history through performance art and conceptual installations involving storytelling and the use of a variety of mediums such as kiln-formed glass, photography and video.

Jerry Takigawa pieces together fragments of his family history through the use of old photographs and artifacts as an examination of his family’s story and the history of the American Japanese diaspora.

Tom Nakashima’s iconic images have metaphorically evolved as the history of world events change. One of his images is that of tree emerging through the roof of a wigwam. The wigwam could be interpreted as shelter, but also as a kind of cage. The tree, usually used as a symbol of natural life form; is not a free tree but a captive one — a bonsai.

Lydia Nakashima Degarrod creates installations which express feelings of displacement using the cotton boll as a symbol for the Japanese presence in Peru, and for the first wave of Japanese immigrants who came to work on the cotton plantations. Each boll contains mulberry fiber and photo etchings of her father and other Japanese Peruvians affected by the actions of the governments of Peru and United States during World War II.

Lucien Kubo uses her artwork to express her views on social change, environmental action and the struggle for social justice, juxtaposing photographs of her family in the American Concentration camp with images of current political concerns.

Wendy Maruyama addresses the forced evacuation and incarceration through the use of social commentary, humor, and sculptural forms. In her E.O. 9066 series, she combines photo images by Dorothea Lange and Toyo Miyatake with objects such as a broken teacup and expressions like No! No! and Yes! Yes! which refers to the so-called “loyalty questionnaire” given to incarcerated Japanese Americans. Those who answered “No” to questions 27 and 28 or who were deemed disloyal, were segregated from other detainees and moved to the Tule Lake Relocation Camp in California.

Masako Takahashi is the only artist in the exhibition who was born in an American concentration camp. She uses her hair to create a single Japanese Zen circle or to stitch long sequences of script on Japanese clothing, silk panels and long rolls of silk fabric. The script is unreadable and undecipherable. Yet, its repetition of form and structure gives the allusion that it may be an actual language. It also may be her way of masking her feelings about the incarceration. She leaves it up to the viewer to decide.

Na Omi Judy Shintani brings to light injustice and invigorates compassion and connections between many different communities that have been labeled ‘the other’ whenever someone has to be scapegoated during times of economic stress and chaos.

Together, at a critical moment in time, these artists bring a dark corner of our country’s collective past to light and show how the power of art can transform even painful personal experience into an expression of the sublime.